Key corruption risks for councillors

- Poorly managed conflicts of interest:

- kickbacks to local businesses owned by associates

- decisions related to grants and planning

- difficulties in appropriately managing conflicts of interest in smaller communities.

- Misuse of position. Section 123 of the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) defines misuse of position by a councillor or member of a delegated committee. This section also creates an offence for this conduct. Misuse of position includes directing or improperly influencing, or seeking to direct or improperly influence, a member of Council staff, as well as disclosing information that is confidential information. IBAC also sees a heightened risk around unauthorised disclosures of information to further political status, campaigns or personal interests.

- Increased bias with councillor voting blocs on issues raised, with limited oversight and means to prevent this conduct. While this behaviour may be in contravention of the Local Government Act 2020, it will not always constitute corruption.

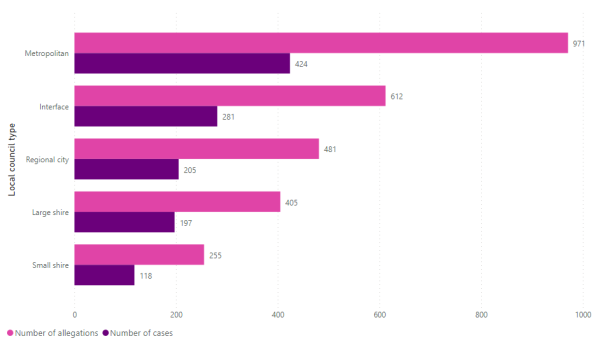

- Electoral donations and political fundraisers connected to councillors’ political parties, particularly in metropolitan and interface councils.

- While council staff are reporting that culture and integrity have been improved, they also perceive councillor conduct to be an area of increasing concern. While the alleged conduct is often in contravention of the Local Government Act 2020, it often would not reach the threshold required for corruption. The alleged conduct could, however, create the conditions for corruption to occur or could be used obscure or cover up corruption if it has occurred, or was occurring.

- Limited councillor preparedness, capacity and skills to deal with emergency situations can increase the risk of corruption and misconduct, particularly in relation to grants or emergency relief and response.

Key corruption risks for council staff

- Fraudulent procurement – contract or purchase order variations as well as misuse of contingency funds.

- Misuse of council assets – cars, machinery and technology.

- Misuse of grant funding – emergency relief and recovery funding.

- Improper influence – receiving gifts and hospitality.

- Favouritism – recruitment; issuing of licenses, permits of approvals; or procurement.

Key general corruption risks for local government

- Organised crime groups cultivating relationships with council staff and councillors to gain access to information, systems or commodities. Local councils hold valuable personal identifying information (such as addresses, phone numbers etc) and decisions by council can have monetary impacts on businesses and individuals.

- Increased risk of information misuse due to work from home arrangements. The opportunities to disclose information without detection are greater than before, and there is an increased risk of cyber security threats due to remote working.

- Increased risk of improper influence in land/planning decisions within regional/rural councils experiencing population growth due to COVID-19.

- Misuse of funding for personal gain or manipulation of reporting against funded services or programs.

Key insights from allegations

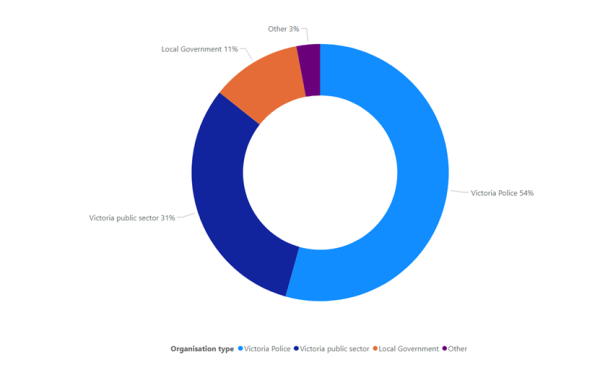

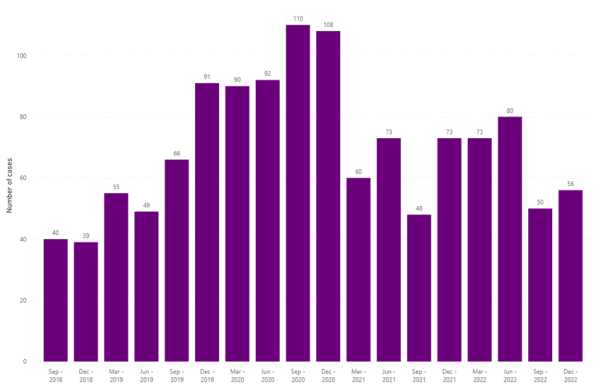

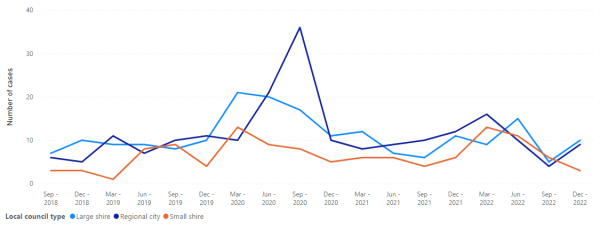

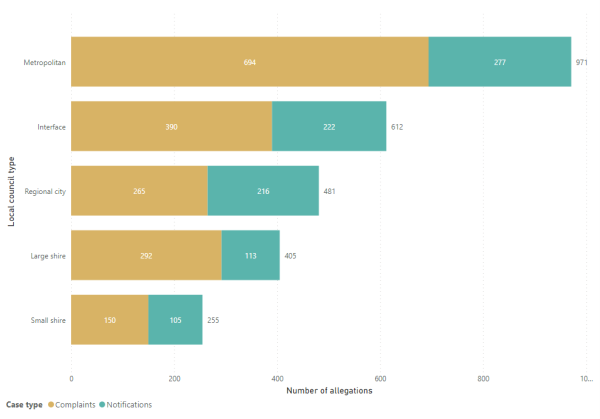

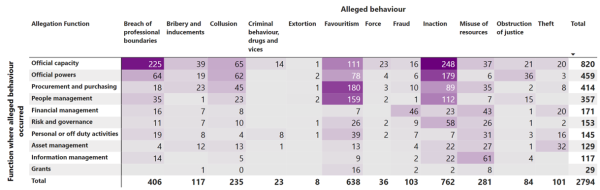

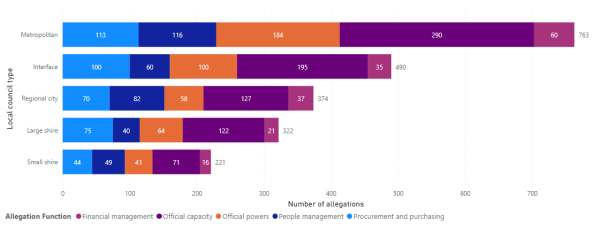

Approximately 11% of all allegations received by IBAC relate to local government. IBAC classifies all allegations it receives against its Behaviours and Activities Model. Some of the most common types of allegations in local government are often not about corruption:

- inaction in relation to local council’s official capacity or powers. Often this is a failure by the council to take sufficient or appropriate action in response to licensing or zoning requests, complaints or reports made by residents.

- favouritism (including mismanaged conflicts of interest) in procurement and purchasing, recruitment activities, and planning decisions

- breach of professional boundaries (including bullying and harassment as well as the exceeding of delegated powers), particularly between councillors and in relation to how councillors and other decision makers at council interact with staff and the community.

Key prevention and detection strategies

- Clear and universally understood policies, in line with the Local Government Act 2020 (Vic), for identifying, reporting and managing conflict of interest policies

- Separation of duties for designing and applying the planning scheme. For example, IBAC’s recommendations for reform arising from Operation Sandon.

- Separation of duties and approvals for employees involved in procurement

- Regular audits to check compliance with policies and procedures

- Secure information management systems and a positive information security culture

- Practices to encourage and support councillors and staff to speak up and report suspected corruption and misconduct

- Conducting regular audits to look for trends and patterns in the awarding of funds, such as community grants

- Mandatory regular training and awareness raising to be conducted for employees and contractors.