Key corruption risks

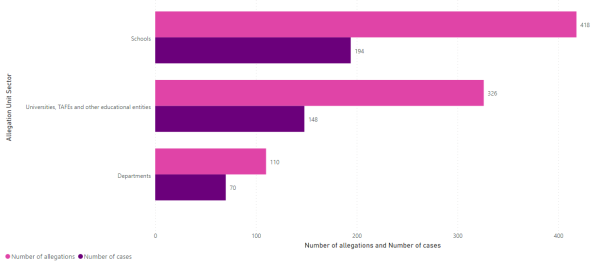

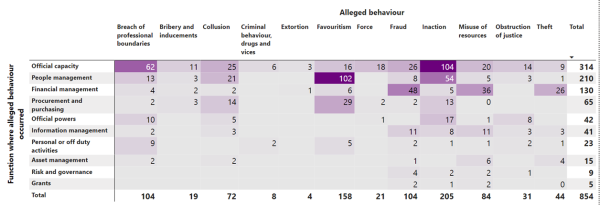

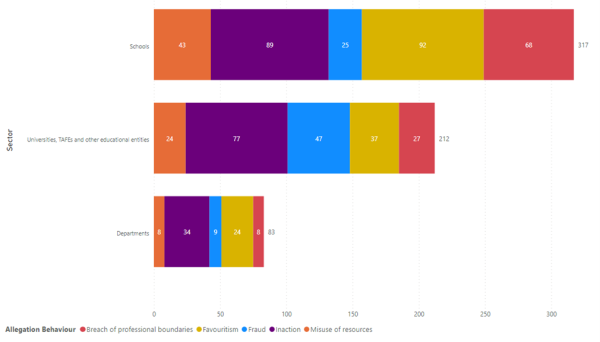

Schools

- Financial management, including the misuse of school funds, fraudulent invoices to receive funds and misuse of payroll, leave and allowances.

- Teachers’ interactions with students and parents, as well as other staff. IBAC receives many allegations about teachers’ poor conduct although they may not meet the threshold of corruption.

- Recruitment and promotion, as well as complaints management.

Universities, TAFEs and other educational entities

- People management, including recruitment and promotion. This also includes the application processes for students.

- Interactions between staff and students, including staff acting inappropriately towards students and for their own benefit.

- Information management, including unsecure networks open to exploitation or attacks.

Departments and statutory authorities

- Procurement and purchasing, particularly ongoing contract management and selection processes.

- Complaints management.

Construction and capital works for educational facilities

- Contract management (and contractual oversight) of services delivered.

- Procurement and regulation.

- Major infrastructure projects, encompassing the aforementioned risks, particularly procurement fraud.

Key drivers of corruption risk

Schools

- Limited awareness about corruption, prevention and reporting strategies.

- Lack of adherence to the frameworks for the management of conflict of interest in recruitment and procurement.

- Inadequate leadership culture that leads to overall development, or perception, of a discriminatory, bullying or non-transparent culture in a school.

Universities, TAFEs and other educational entities

- Uncoordinated and inconsistent processes across divisions that make it difficult to detect anomalies.

- A lack of active management of employees allows for misconduct to continue unchecked.

- Inadequate or inexperienced board and governance structures within registered training organisations and universities, including attracting board members with appropriate experience and capability.

Departments

- Perceptions within sections of the portfolio on the ability to investigate and communicate the outcomes of investigations into corruption and misconduct, leading to a reduction in the willingness of employees to report.

- The sector’s large size, and the wide variety of entities within it, creates challenges for identifying agency-specific risks and both formulating and monitoring tailored integrity initiatives .

Key prevention and detection strategies

Pleasingly, IBAC’s 2022 Perceptions of Corruption Survey of the Public Sector found that 37% of public sector employees who responded believe their organisation performs very well when it comes to ensuring strong policies, procedures and controls are in place. 40% considered it to be adequate.

The following strategies are for consideration of all public bodies in the education sector:

- Strong integrity frameworks that identify perceived, potential or actual conflicts of interest, as well as how they should be managed.

- Proactive measures, such as mandatory and regular training and awareness raising to ensure staff – including private sector employees – are aware of and understand integrity-related policies and procedures.

- Robust recruitment policies and procedures to ensure integrity from shortlisting, panel selection and vetting, through to induction.

- Regular and random audits to ensure compliance with policies and procedures in risk areas such as procurement, recruitment and information security).

- Building a positive ‘speak up’ culture built on an integrity framework, and a leadership culture that leads by example.