- Oversight of police misconduct in Victoria is a mixed civilian review system, under which both Victoria Police and IBAC have a role in receiving, handling, assessing and investigating complaints about police misconduct. Victoria Police’s Professional Standards Command (PSC), which in June 2023 has 195 police officers and 35 public service staff, has a significant role in investigating police misconduct. IBAC has a role in investigating the most serious matters. Other matters IBAC refers to PSC, many of which are subject to active monitoring or review by IBAC.

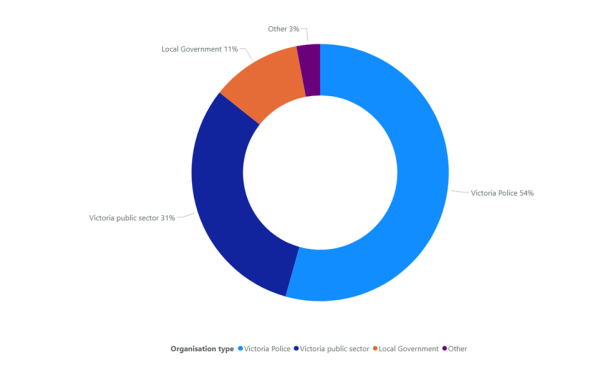

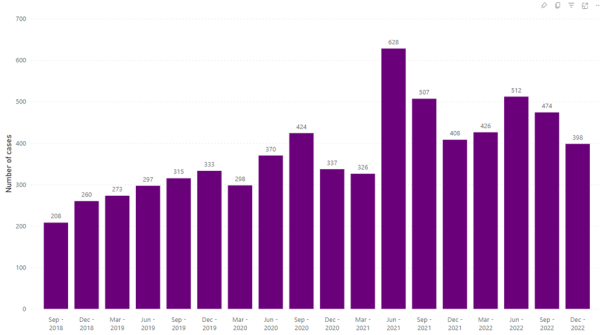

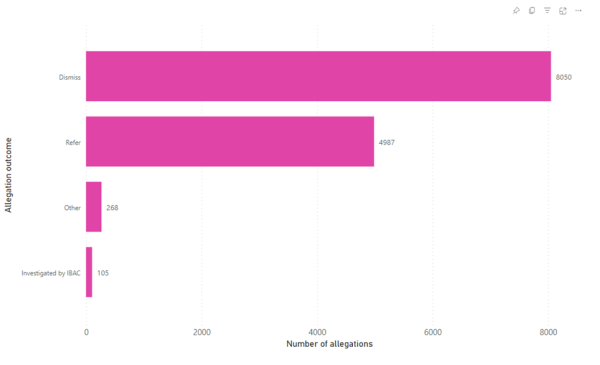

- Approximately 54% of allegations received by IBAC between 1 July 2018 and 31 December 2022 relate to Victoria Police. This is partly due to policing’s specific corruption and misconduct risks and challenges, which are linked to the significant powers police are given to keep the community safe, as well as IBAC’s police oversight role. IBAC investigates approximately 1% of allegations received against Victoria Police, due to IBAC’s legislated requirement to prioritise serious and systemic police misconduct and corruption and resourcing constraints, with 60% of allegations received by IBAC dismissed. In accordance with the IBAC Act, 37% of allegations were referred to Victoria Police as the more appropriate body to investigate, with many of these marked for IBAC to review once completed.

- Approximately one quarter of IBAC’s investigations into police involve allegations of excessive use of force, with many of these focused on Victoria Police interactions with people who are diverse or experience vulnerability or marginalisation. These investigations can result in court action and recommended prevention actions for Victoria Police to implement to minimise the risk of excessive use of force.

- Improper police responses to, or investigations into, police perpetrated family violence and predatory behaviour continue to be a focus for IBAC due to it being an issue of serious police misconduct that presents severe risk to public confidence in police. Additionally, these cases have an increased risk of poorly managed conflicts of interest. This includes the risk of investigations into police personnel being poorly handled due to the impact that any criminal charges/outcomes may have on a police officer’s employment. Recent changes to Victoria Police policy and the establishment of a dedicated unit within Victoria Police to investigate these incidents will be monitored by IBAC to ensure effective implementation.

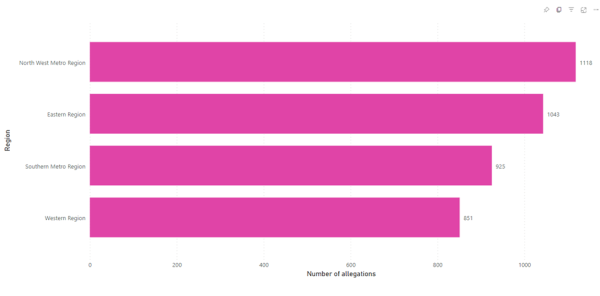

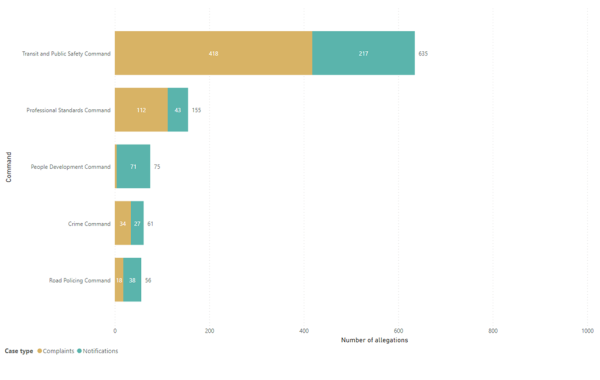

- The number and type of cases and allegations received by IBAC about particular stations in the four Victoria Police regions and particular units within Commands and Departments are often influenced by the relative size and population of the areas they cover, the number of personnel and their levels of interaction with the community.

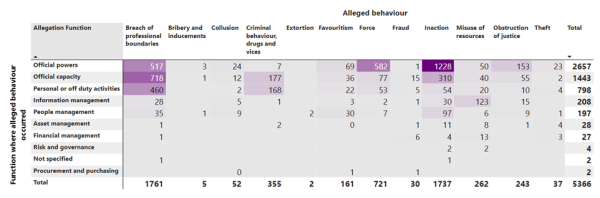

The most common types of alleged behaviour

- Inaction – such as, failure to take sufficient or appropriate action, failure to obey instructions or policies and failure to properly investigate

- Breach of professional boundaries – such as, rudeness, bullying and harassment and exceeding delegated powers

- Force – such as physical violence and threats

- Criminal behaviour – such as sexual harassment or offences, breach of court orders and stalking

- Misuse of resources – such as unauthorised disclosure, disposal, use or access of information.

Key enduring police misconduct and corruption risks

- Excessive use of force

- Favouritism, including poorly managed conflicts of interest

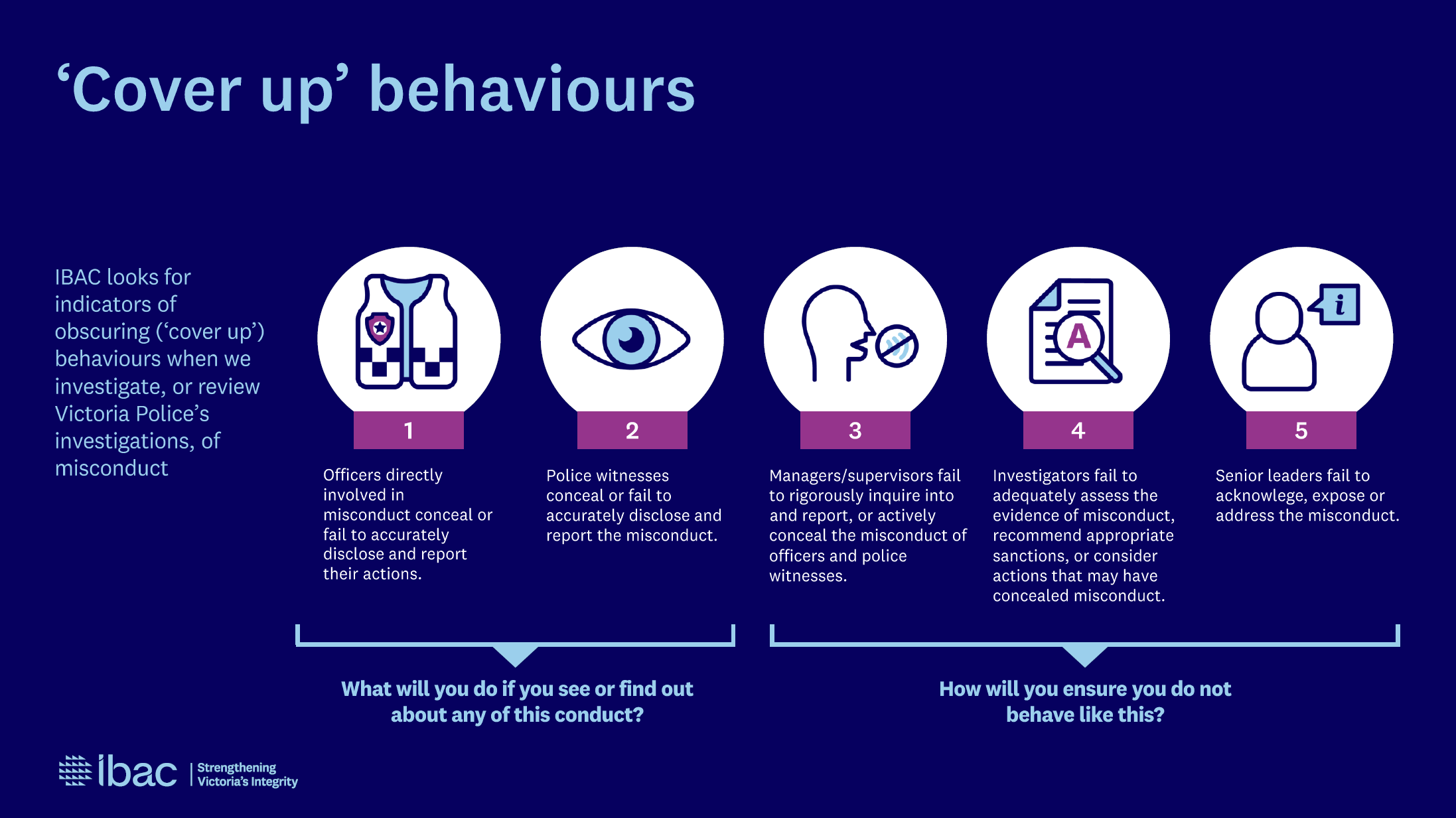

- Inaction, including obscuring behaviours such as failure to investigate or report colleagues’ misconduct or lying to protect a colleague

- Organised crime infiltration of police or police having friendships or other associations with criminals

- Use of illicit drugs which exposes officers to blackmail and compromise

- Misuse of resources, particularly the unauthorised access and disclosure of police information for personal benefit

- Predatory behaviour or other abuses of position for a sexual purpose, and sexual harassment

- Bullying and harassment.

Key prevention and detection strategies

- Early intervention in complaints management

- Effective use of force recording and analysis

- Strong conflict of interest and declarable association frameworks

- Information security management including effective systems and audit regimes

- Risk assessment strategies underpinned by regular training and audits

- Regularly reinforced policies and procedures

- Positive workplace culture, including the fostering of a ‘speak up’ culture and protections for public interest complainants

- Ethical leadership from all ranks.