Key corruption risks (for entire sector – both government agencies and funded organisations):

- poorly managed conflicts of interest, including by employees providing services to their communities

- fraud, for example in the areas of managing and reporting on the use of funding

- theft of funding or assets

- misuse of resources

- bribery, for example to receive services or reduce waiting periods for services, for example in social housing.

Key corruption risks (for community service organisations):

- conflicts of interest in board governance and recruitment

- poor oversight of financial payments and misuse of funding

- limited systems and controls

- poor governance and poor understanding of roles and responsibilities.

Key prevention and detection strategies:

- strong conflict of interest frameworks

- information security management

- procurement policies and procedures

- risk assessment strategies underpinned by regular training and audits

- regular and random audit regimes

- positive workplace culture, including the regular reinforcement of appropriate behaviour and reporting of improper conduct

- comprehensive education and training schedule for staff and boards, including training on governance

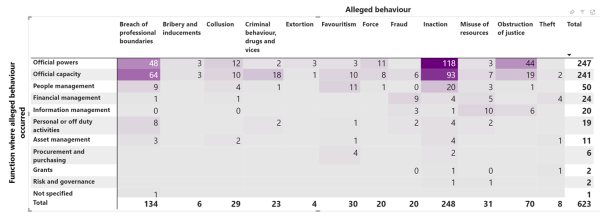

Most common types of allegations:

- Inaction in relation to the official powers by an organisation or employee (such as inadequate care or custody, a failure to investigate complaints). This could also be an organisation or individual failing to act to meet their obligations or to carry out certain responsibilities.

- Breach of professional boundaries (including bullying, harassment and discrimination) in relation to official capacity (including how staff interact with one another and clients) and official powers (including custody and care, investigations and enforcement activity)

- Obstruction of justice, interfering with a witness, such as in a formal investigation

- Misuse of resources, unauthorised use, and unauthorised disclosure of information or disposal (such as inappropriate disposal of assets)

- Favouritism, seeking or showing preferential treatment and hiding or failing to disclose a conflict of interest

- Collusion, manipulate a process (like a recruitment or procurement process)

- Fraud in financial management

- Force including intimidation or coercion, threats or physical force.

- Corrupted or improper recruitment and promotion processes, and complaints management (such as internal investigations)

- Information management, including unauthorised access, alteration, use, disposal, and release of information

- Personal or off duty activities that include inappropriate associations, for example with members of the community which would create a conflict of interest.