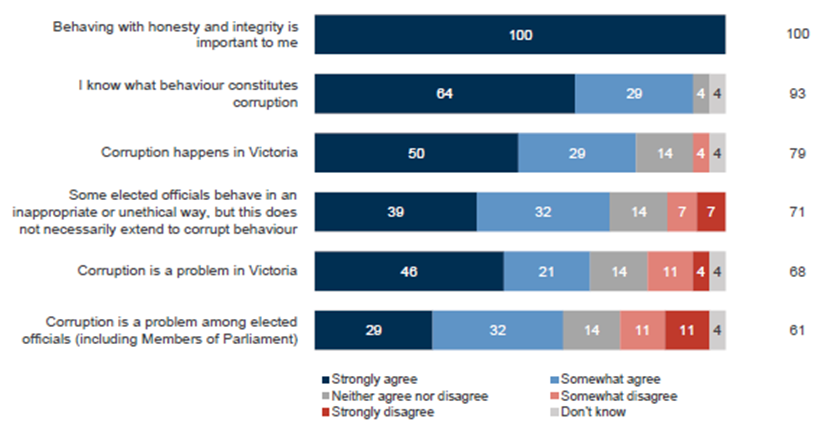

Most MPs agree that they know what behaviour constitutes corruption.

Ninety-three per cent agree that they know what behaviour constitutes corruption, four per cent neither agree or disagree and four per cent don’t know. This finding is similar to the Councillor cohort who were also surveyed in 2023.

MPs value honesty and integrity.

This is evidenced by the universal agreement that ‘behaving with honesty and integrity is important to me’ (100% strongly agree).

Over three in five believe corruption is a problem in Victoria and is also a problem among elected officials.

MPs were asked a series of questions to understand to what extent they believe corruption happens and is a problem.

- Overall, 79 per cent agree that corruption happens in Victoria and almost seven in ten (68%) agree that corruption is a problem in Victoria.

- Slightly fewer MPs (61%) agree that corruption is a problem among elected officials (including MPs), with only 11 per cent strongly disagreeing. This result is similar to the percentage of Councillors reporting corruption is a problem among elected officials (including Councillors) (59%).

- There is however a relatively high level of agreement (71%) that some elected officials behave inappropriately or unethically although not necessarily corruptly.

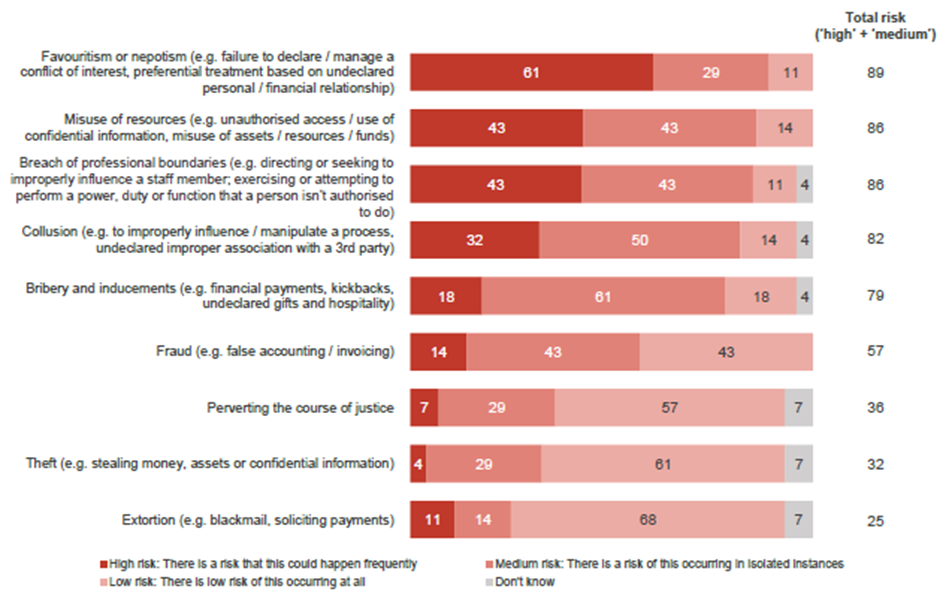

Favouritism, misuse of resources and breaches of professional boundaries are viewed as the most common risks facing MPs.

MPs were asked to describe (through an open response question) the most significant ways in which elected representatives in State Parliament might be vulnerable to corruption. The key areas cited include a conflict of interest, political interference and control, bribery and fraud, and misappropriation of funds. Comments also focus on financial pressures, being misleading and ignorance.

The top three improper behaviours that MPs perceive to be a high risk of occurring are favouritism or nepotism, misuse of resources, and breaches of professional boundaries – over 86 per cent of MPs identified these behaviours as a high or medium risk. Over sixty per cent considered favouritism or nepotism to be a high risk.

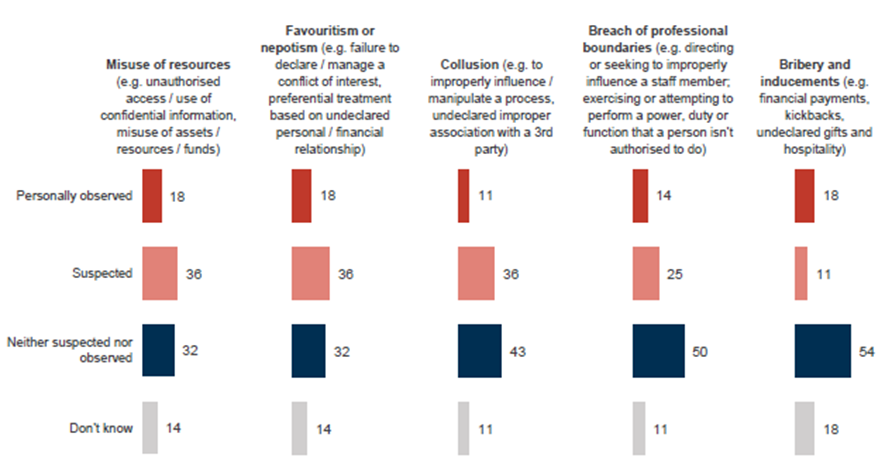

The extent to which MPs have personally observed or suspected that improper behaviours are occurring in State Parliament varies by type of behaviour.

Close to one in five MPs (18%) have personally observed instances of favouritism or nepotism in the last 12 months in State Parliament and 36 per cent suspect this has occurred. The same percentages report having personally observed or suspected misuse of resources. Eighteen per cent also reported having have personally observed bribery or inducements. This is higher compared to the Councillor cohort (5%) and no public sector employees reported having observed bribery or inducements in the previous 12 months.

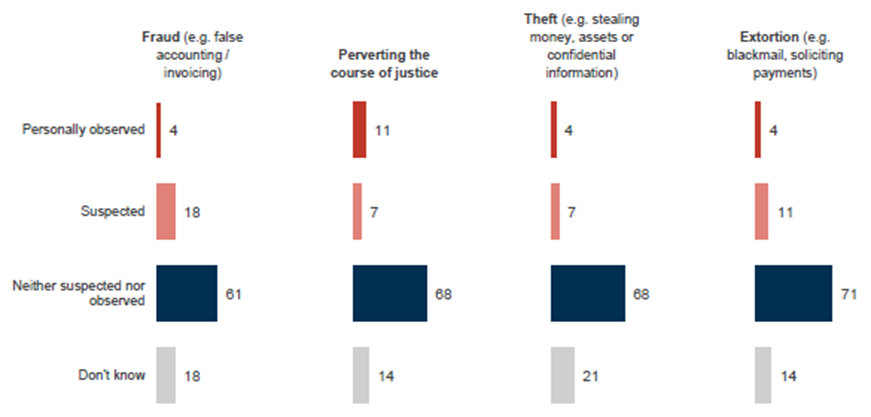

Fewer MPs have suspected or observed occurrences of theft, fraud or extortion within State Parliament. However compared to other cohorts, MPs are more likely to have personally observed or suspected fraud or extortion (eg 21% of MPs has observed or suspected fraud compared to 8% of Councillors and 11% of public sector employees).

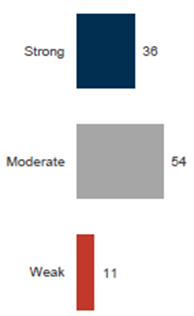

The majority of MPs describe the ethical culture of State Parliament as ‘strong’ or ‘moderate’.

Ninety per cent of MPs describe the ethical culture of State Parliament as ‘strong’ or ‘moderate’. This is higher than public sector employees (84%) and Councillors (78%).

MPs express a range of views regarding the ethical culture of Parliament. Among those who consider the culture is ‘strong’, the reasons are based on individual integrity and ethics coupled with the desire to serve the community. Those who rate the ethical culture as ‘weak’ describe self-interest, personal agendas and the behaviour of others as undermining ethical values and culture.

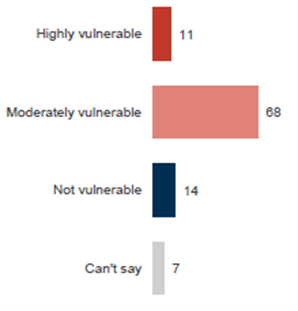

The majority perceive State Parliament to be ‘highly’ or ‘moderately’ vulnerable to corruption.

When asked to consider the ethical culture, internal controls and any specific risks that the MPs perceive as relevant, 79 per cent identified State Parliament to be highly or moderately vulnerable to corruption. Only 14 per cent rated it as ‘not vulnerable’ to corruption. MPs were significantly less likely to consider there was no vulnerability (14%) compared to Councillors (37%) and public sector employees (32%).

Definite guidance can be lacking when advice is sought on corruption.

Half of MPs (54%) agree that it is difficult to obtain definite guidance when seeking advice on corruption, compared to 25 per cent who disagree.

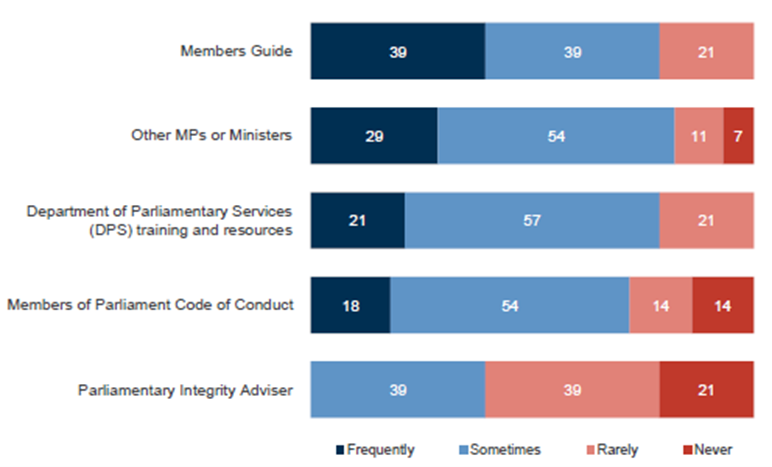

The Members Guide and other MPs or Ministers are most commonly used to better understand their roles and conduct expectations.

When asked what resources they most commonly use to understand their role and expectations regarding conduct, MPs most frequently reported using the Members Guide (39% of MPs use this frequently), followed by other MPs or Ministers (29%). This indicates informal mechanisms are used to understand expectations of conduct.