This is a summary of the Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission’s (IBAC) Local government integrity frameworks review.

This research report provides a snapshot of the integrity frameworks examined in a sample of six Victorian councils and highlights examples of good practices and possible areas for improvement. A key objective of the review is to help all councils review and strengthen their own integrity frameworks, to improve their capacity to prevent corrupt conduct.

The review builds on earlier work published by IBAC in 2015, which reviewed integrity frameworks in a different sample of councils.1

Background

Corruption in local government can lead to increased costs and reduction in economic growth, diminished trust in councils and jeopardise the delivery of valuable programs and services.

Victorian councils provide a wide range of public services and maintain considerable public infrastructure. Collectively, they manage approximately $84 billion in public assets and spend around $7 billion on the provision of services annually.2

Given the resources and responsibilities entrusted to councils, it is important they develop, implement and maintain strong integrity frameworks, and continuously improve their capacity to identify and prevent corrupt conduct.

An integrity framework brings together the instruments, processes, structures and conditions required to foster integrity and prevent corruption in public organisations.3 Integrity frameworks include elements of risk management, management and commitment, deterrent and prevention measures, detection measures, and staff education and training.

Methodology

Six councils participated in this project, comprising a mix of metropolitan, regional and interface4 councils.

The review was undertaken in four phases including stakeholder consultations, an organisational integrity framework survey (which asked participating councils to describe their integrity frameworks), a review of council policies and procedures, and a council staff questionnaire.

A total of 648 responses were received to the questionnaire across the participating councils (a 26 per cent response rate). IBAC also met with participating council CEOs and senior officers to discuss the key findings of the review and to explore specific issues.

The review was limited to council employees, and did not include elected councillors.

Risk management

Risk management helps identify internal weaknesses that may facilitate corruption. However, appropriate controls can reduce the number and severity of instances of corrupt conduct.

All six councils had a risk management policy supported by either a risk management strategy, framework or plan. Their approaches reflected an understanding of the need for responsibility for risk management to be embedded across their organisations. For example, each of the six councils’ policies detailed risk management accountabilities at the executive, senior manager and employee levels.

Three councils had internal risk management committees (and separate audit committees); the other councils had combined audit and risk committees. Only one council’s risk management committee had explicit responsibility for corruption prevention strategies. However, four of the six councils advised they conduct specific risk assessments of potential corruption and fraud risks.

All six councils maintained a risk register detailing strategic and operational risks. Five councils provided information on fraud and corruption risks from their registers. Some councils included ‘fraud and corruption’ as a high-level risk only. Other councils referred to corruption risks relating to specific processes or activities (eg collusion in tender processes).

Good practice observed in this review included:

- establishing a comprehensive risk management framework comprising policies and plans with clear accountabilities for managing risk, including a designated risk management officer

- embedding risk management accountabilities in managers’ position descriptions

- undertaking periodic assessments of corruption and fraud risks across council’s operations

- establishing clear processes for reporting fraud and corruption risks, with regular reporting and senior management oversight of these risks and their controls.

Fraud and corruption control

All six councils had fraud and corruption control frameworks in place with clear accountabilities for the prevention of fraud and corruption at all levels of the organisation.

As part of their frameworks, four councils had fraud and corruption control plans in place or were in the process of developing a plan (compared with only one council in IBAC’s 2015 review). The current review also identified prevention, detection and response measures including processes for identifying fraud and corruption risks, usually through risk assessment processes, risk registers, controls and training.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- establishing a comprehensive fraud and corruption control framework comprising policies, plans and clear accountabilities for fraud and corruption prevention which extends beyond financial fraud

- nominating a senior officer who has overall responsibility for fraud and corruption control in the council who reports to the executive, and audit and risk committee

- providing clear examples of fraud and corruption in relevant policies and procedures, to help employees identify and report suspected fraud and corruption

- developing staff awareness of fraud and corruption risks through induction processes, regular training, and information and resources for employees.

Corruption risks

IBAC’s review examined the councils’ policies and procedures in relation to seven corruption risks – procurement, cash handling, conflicts of interest, gifts, benefits and hospitality, employment practices, misuse of assets and resources, and misuse of information.

IBAC also asked the six councils to rate each of these risks as a high, medium or low corruption risk. One council rated misuse of assets as a medium-to-high risk. The six other risks were rated by the councils as low or low-to-medium, primarily because the councils considered they had sufficient controls in place.

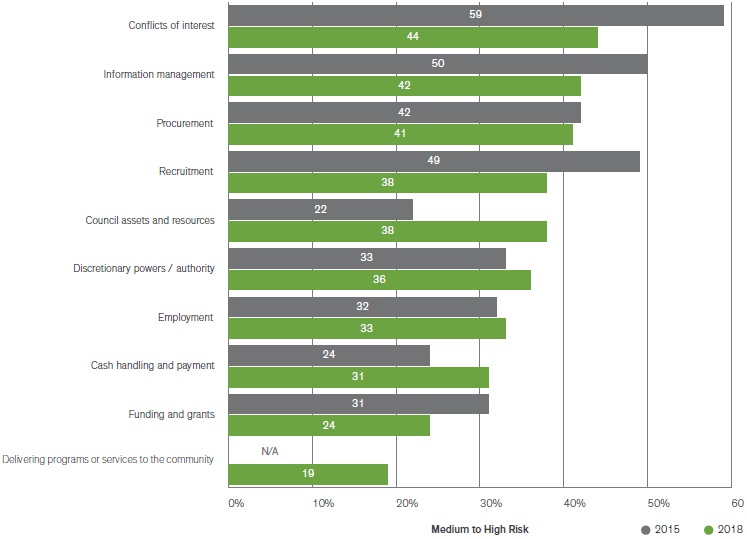

Council employees were also surveyed about their perceptions of the extent to which a range of functions or activities were a corruption risk. The functions and activities considered by respondents to be at highest risk of corruption (specifically, as a medium-to-high risk) were conflicts of interest, information management and procurement.

Risk area 1: Procurement

Corruption in public sector procurement has been identified as a recurring issue in IBAC investigations. Common vulnerabilities include the failure to manage conflicts of interest, lack of supervision and a failure to comply with procurement policies. It is important that councils are alert to the risks associated with procurement, and have solid procurement policies and procedures in place to mitigate this risk.

All six councils had sound procurement policies and procedures in place. Common controls in these documents included requiring members of tender panels to declare conflicts of interest; discouraging the acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality from suppliers; ensuring prospective suppliers have equal access to information; and segregating duties. Councils need to be vigilant that these controls are applied and are working effectively.

Councils can also do more to ensure suppliers better understand the standards expected of them, and of council employees. There is merit in councils outlining expectations of suppliers through a supplier code of conduct (noting that the Victorian Government has implemented a code of conduct for suppliers in state government). Such a code could outline requirements around integrity, ethics and reporting suspected corrupt conduct.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- requiring tender panel members to complete conflict of interest and confidentiality declarations at key points in the procurement process (eg before opening tender submissions, and after tender evaluations but before recommendations are made)

- requiring tender evaluation panels to have at least one independent member

- providing clear guidance to prospective suppliers regarding their obligations in relation to conflicts of interest and gifts, benefits and hospitality

- expressly prohibiting employees from soliciting gifts from suppliers and requiring employees to report all offers from suppliers.

COUNCIL STAFF QUESTIONNAIRE – SCENARIOA council employee who manages the tender process tells a friend who runs a concreting business about an upcoming council tender and provides confidential council information so that their friend has an edge over other tenderers. Ninety-three per cent of council staff correctly considered the conduct in this scenario to be corrupt conduct. Sixty-five per cent of council staff said they would report this conduct internally within their council. |

Risk area 2: Cash handling

Cash was a method of payment at all six councils, however dedicated cash handling policies were only identified in four councils. Although the amount of cash handled by councils varied (and may be minimal as councils seek to minimise the associated risks), it is appropriate that written procedures clearly outline the processes and obligations on employees who handle cash, to avoid risks of theft.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- requiring employees with cash handling responsibilities to undertake pre-employment screening checks as part of the selection process

- establishing clear procedures which outline when employees can claim petty cash, reimbursement limits and approval processes

- establishing a range of controls to mitigate risks associated with cash handling, including conducting regular and random audits of cash holdings.

Risk area 3: Conflicts of interest

Failure to properly identify, declare and manage conflicts of interest has been a common feature of IBAC investigations. When conflicts of interest are not properly identified and managed, they provide opportunities for corruption, placing a council’s finances and reputation at risk. Public sector agencies, including councils, need to be alert to the risks associated with failing to properly manage conflicts of interest.

Some of the six councils highlighted good practice around the identification and management of conflicts of interest in relation to their recruitment and procurement activities, but there are opportunities to strengthen policies and procedures.

Only one council had a tailored, stand-alone conflict of interest policy. The other councils relied on general guidance provided by Local Government Victoria or their own codes of conduct to communicate information on conflicts of interest. It was not always clear how employees should declare or manage conflicts of interest.

It is important that councils develop and communicate a clear policy that outlines what conflicts of interest are, and how employees should declare and manage conflicts. It is also good practice to centrally monitor and oversight conflicts of interest, for example, through a register.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- highlighting the importance of declaring and managing conflicts of interest (including through the use of examples and checklists) in codes of conduct

- providing clear guidance on how to manage conflicts of interest in high risk functions and activities, including procurement and recruitment

- maintaining a central conflict of interest register

- requiring contractors and council planners to identify, declare and manage conflicts of interest.

Risk area 4: Gifts, benefits and hospitality

The acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality can create perceptions that an employee’s integrity has been compromised. It is a particular risk in procurement as it can undermine both public and supplier confidence in the process.

Five councils had stand-alone policies or procedures providing guidance on gifts, benefits and hospitality. Gifts, benefits and hospitality were also addressed in codes of conduct and some councils covered this issue in their procurement policies, although the strength of the message (discouraging the acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality from suppliers) varied.

All six councils maintained gifts, benefits and hospitality registers, however there was little indication that the councils were regularly monitoring their registers to identify potential risks or vulnerabilities.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- developing a policy that clearly outlines the council’s position on gifts, benefits and hospitality including employee obligations in relation to gifts, benefits and hospitality

- ensuring policies on gifts, benefits and hospitality are broad in scope and apply to all employees and personnel acting on behalf of the council

- requiring employees to declare gifts, benefits and hospitality regardless of whether they are accepted or declined and recording all offers, regardless of whether they are accepted or declined

- requiring all offers from suppliers to be declared, regardless of their value, and recording this information on the gifts, benefits and hospitality register.

Risk area 5: Employment practices

IBAC has identified that employment practices are vulnerable to corruption, including recruitment compromised by conflicts of interest and inadequate employment screening. This can result in the ‘recycling’ of employees with problematic discipline and criminal histories.5

The six councils advised they mitigate risks associated with recruitment by conducting pre-employment screening checks on candidates, usually involving police checks, reference checks and verification of qualifications. Some councils had stronger pre-employment checks for positions considered ‘high risk’ (such as those in finance, information services, and planning and development). The councils also had controls in place to promote merit-based recruitment, including the use of independent panel members and conflict of interest declaration processes.

However, there appeared to be a lack of awareness of other potential risks associated with employment, such as the recycling of problematic employees. There is also scope for councils to strengthen controls and improve employee awareness of policies and processes around secondary employment.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- conducting pre-employment screening checks, particularly for high-risk positions

- requiring recruitment panel members to withdraw from a panel where a conflict of interest exists or is perceived to exist

- clearly articulating that secondary employment can create a conflict of interest and therefore approval is required to undertake external employment

- an advisory committee (with an independent chair) advising council on matters of CEO performance, contract extensions, remuneration matters and recruitment.

Risk area 6: Misuse of assets and resources

Assets and other resources of an organisation can present a corruption risk, through theft and misuse. Both high and low-value resources can present corruption risks, as highlighted by IBAC’s 2015 Review of council works depots.6

All six councils had policies and procedures around the appropriate use of various council assets and resources, including the use of motor vehicles, fuel cards and corporate credit cards, and minor assets. All six councils also communicated to their employees about appropriate use of resources in their codes of conduct.

The councils advised they have controls to mitigate risks associated with the misuse of assets and resources. For example, three councils maintained registers or systems for managing minor (low value) assets. This is good practice, however, there were some limitations including one council not allocating a unique identifier to all assets.

Councils varied in how strongly they communicated to employees that the misuse of council property is not appropriate. In an example of good practice, one council prohibited personal use of small plant and equipment, and communicated that message in tool box meetings, through memos and staff inductions.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- clearly stating that fraudulent or unauthorised use of council assets and resources will be subject to the council’s disciplinary code and possibly criminal prosecution

- maintaining registers or systems for managing low value assets including, for example, IT equipment, and small plant and equipment

- undertaking regular and random audits of council assets and resources, eg checking motor vehicle log books and auditing fuel card usage

- developing clear policies and controls around the disposal of surplus or scrap material and assets (regardless of value).

COUNCIL STAFF QUESTIONNAIRE – SCENARIOA senior council employee is a member of the local football club. They arrange for the club to borrow council equipment without authorisation to maintain the clubhouse at no charge. This saves the club thousands of dollars each year. Eighty-eight per cent of council staff correctly considered the conduct in this scenario to be corrupt conduct. Sixty-four per cent of council staff said they would report this conduct internally within their council. |

Risk area 7: Misuse of information

IBAC has identified unauthorised information access and disclosure as a risk across the Victorian public sector. This includes access and disclosure by employees with high levels of access to information such as system administrators or IT specialists. Unauthorised information access and disclosure are enablers of corrupt conduct and can be overlooked as corruption risks by agencies.

All six councils had policies and procedures relevant to the appropriate use of information and information systems. Some councils also had stand-alone information security policies. Each council’s code of conduct also provided guidance on the appropriate use of council information and information systems and/or the importance of privacy and confidentiality. However, only three councils included risks relating to information misuse on their risk registers.

Councils provided examples of controls to mitigate risks around information misuse, including user access controls (such as restricted access, user access reporting and password sharing controls) and network security and system control audits.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- highlighting information misuse as a risk in fraud and corruption prevention policies and plans

- developing a stand-alone information security policy which addresses confidentiality, integrity and unauthorised access to sensitive information

- providing guidance on the appropriate use of council information and information systems and/or the importance of privacy and confidentiality in employee codes of conduct

- requiring new employees and members of tender evaluation panels to sign information confidentiality agreements.

COUNCIL STAFF QUESTIONNAIRE – SCENARIOA council employee helps their spouse set up a mailing list for their veterinary clinic by obtaining the addresses of registered pet owners from a council database. Ninety per cent of council staff considered the conduct in this scenario to be corrupt conduct. Seventy-two per cent of council staff said they would report this conduct internally within their council. |

Ethical culture and leadership

People in leadership positions set the ethical tone of an organisation and are key to building organisational integrity and corruption resistance. It is essential that they communicate expected standards of behaviour and values to staff, lead by example, appropriately supervise employees, and act on suspected misconduct or corrupt conduct. Managers should also actively encourage staff to report suspected corrupt conduct and reinforce that reprisals for making disclosures will not be tolerated.

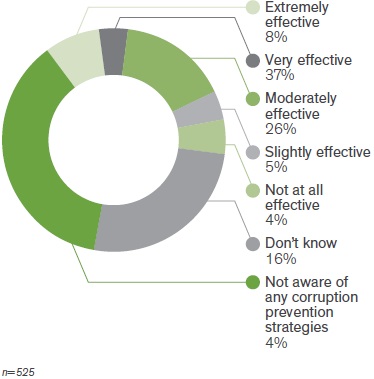

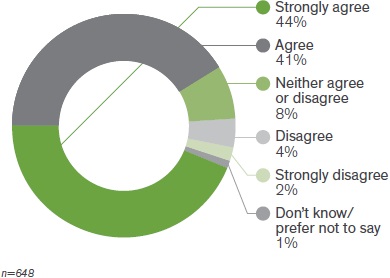

Eighty-five per cent of respondents to the staff questionnaire ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that the culture at their council encourages people to act with honesty and integrity. Nearly two-thirds of respondents considered their council to be ‘moderately’ or ‘very effective’ at preventing corruption.

As required by the Local Government Act 1989, each council maintained a code of conduct which outlined the behaviours and standards expected of employees. The codes made reference to either corrupt conduct or fraud, and covered key risks, although there was generally a greater focus on fraud than corruption.

It is good practice to be explicit about corruption, misconduct and fraud by providing definitions and examples, to assist employees’ understanding. Most codes expressly stated that unlawful actions may lead to criminal charges and/or civil action. Four councils also required employees to sign a form acknowledging that they had read and understood the code. This is one way of promoting understanding of the required standards of conduct.

Four councils had a dedicated senior representative as a central point of contact for fraud and corruption prevention in their organisation. In three of these councils, the senior officer was a member of the executive management team and attended audit committee meetings. Senior management in some councils also have responsibility for protected disclosures and welfare management.

All six councils provided a range of education and training to staff including in relation to fraud and corruption awareness, risk management, procurement and protected disclosures. Two councils provided a tailored online e-learning module on fraud and corruption awareness. The training included examples of corrupt conduct and how to report suspected corruption or fraud.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- including statements in employee codes of conduct from the CEO that emphasise the importance of understanding and complying with the code, and using it to guide ethical decision making

- nominating senior officers to have overall responsibilities for risk management, fraud and corruption control and for protected disclosure and welfare management

- maintaining a commitment to education and training, including regular training to employees on fraud and corruption awareness, risk management, procurement and protected disclosures.

It starts from the quality, ethics, character, principles and commitment of the CEO to drive positive culture change and to then ensure that the right staff are employed … the CEO is the one who sets the tone of the council as an organisation

- Council employee

Reporting

An integrity framework must include mechanisms to help councils to detect instances of suspected corrupt conduct in a timely manner. It is therefore critical that employees know how to and are encouraged to report suspected corrupt conduct.

All six councils’ fraud and corruption control procedures outlined processes for employees to report suspected fraud and corruption, although these were largely focussed on internal channels (eg managers, CEOs and protected disclosure coordinators). And all of the councils had protected disclosure procedures in place, as required by the Protected Disclosure Act 2012 (PD Act).

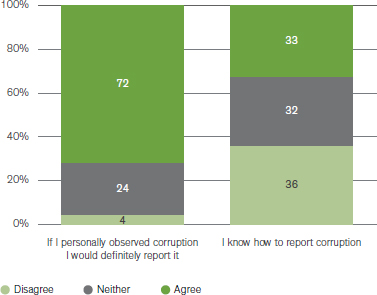

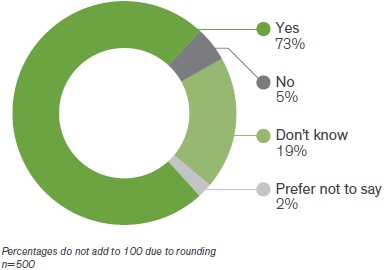

The review highlighted that despite high levels of willingness to report suspected corruption (73 per cent of respondents to the staff questionnaire said they were willing to report), concerns about possible victimisation or other reprisals was still an issue. Almost 30 per cent of respondents were not confident they would be protected from victimisation. The most common reasons for not reporting included fear of reprisal and lack of confidence in senior management to address the issue.

While the current protected disclosure regime (established under the PD Act) has been in place for more than five years, less than half of respondents said they were aware of their council’s protected disclosure procedures, and only a quarter said they had received information or training on protected disclosures in the past 12 months.

To encourage reporting, councils need to do more to improve employees’ awareness of how to make protected disclosures and the protections available to them to encourage reporting. Councils should also ensure employees understand they can report directly to IBAC.

The requirement of the council CEO to mandatorily report suspected corrupt conduct to IBAC pursuant to section 57(1) of the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2011 should also be consistently outlined in appropriate policies.

Good practice observed in this review included:

- audit and risk committees reviewing reports of suspected corrupt conduct as a standing agenda item

- ensuring relevant policies and procedures outline both internal and external channels for reporting

- appointing a welfare officer to support disclosers or a person who is the subject of the disclosure

- operating a centralised reporting system which can only be accessed by authorised employees, to enhance confidentiality and minimise the risk of reprisals.

[There is] no hesitation about reporting what seems wrong; it is knowing the best channels and feeling confident about protection (and not adversely affecting career prospects) that is the issue. Staff can be ‘shown the door’ in apparently legit ways or under the guise of other issues.

- Council employee

Conclusion

Victoria’s councils have an important role to play in the provision of services at a local level. If there is corruption, it robs the community of much needed funds to support front line services. Corruption hurts us all.

Public sector agencies need to have strong integrity frameworks comprised of policies and procedures, processes, systems and controls, which promote integrity and help prevent and detect corrupt conduct.

IBAC’s review of integrity frameworks in local councils demonstrated that the six participating councils have sound integrity frameworks in place. However, following discussions with councils, IBAC identified that some good practice in policies had not translated into practice. All councils are encouraged to develop strong policies and procedures, and to ensure compliance.

Our review highlighted instances of good practice as well as opportunities for improvement. It is beneficial for all councils to consider how they can strengthen their integrity frameworks in suitable ways for their organisations.

In particular, councils are encouraged to develop and communicate a clear policy on conflicts of interest, proactively address misconduct and corruption risks associated with employment practices, and ensure suppliers understand the standards expected of them and council employees.

It is also critical to encourage employees to report instances of suspected corrupt conduct and proactively explain to employees how they can be protected, and that their reports will be taken seriously.

1 IBAC 2015, A review of integrity frameworks in six Victorian councils, IBAC, Melbourne.

2 Victorian Auditor-General’s Office (VAGO) 2018, Local Government and Economic Development, VAGO, Melbourne, p.21.

3 Based on the definition developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Integrity Framework, <www.oecd.org/gov/44462729.pdf>.

4 Interface councils are councils surrounding metropolitan Melbourne.

5 IBAC 2018, Corruption and misconduct risks associated with employment practices in the Victoria public sector, IBAC, Melbourne.

6 IBAC 2015, Local government: Review of council works depots, IBAC, Melbourne.