All Victorians should have confidence in the integrity of Victoria Police.

The Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) plays a vital role in building community confidence by providing independent oversight of police operations. This report provides a focused account of IBAC’s key police oversight activities since becoming fully operational in early-2013.

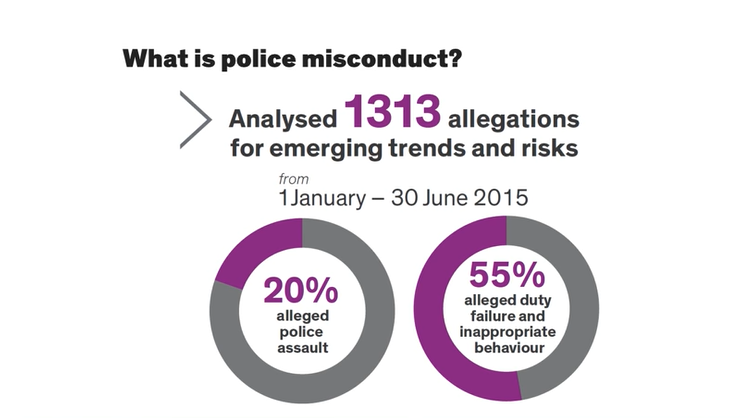

Under the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2011 (IBAC Act), IBAC is responsible for preventing, exposing and investigating police misconduct and corruption. Prevention work includes research and education, both of which are critical to preventing police misconduct and corruption. Our report describes a range of significant strategic projects and initiatives, including an audit IBAC has initiated of Victoria Police’s local complaint handling processes.

IBAC also reviews the outcomes of certain investigations of Victoria Police matters. Some of these reviews are routine; others are sensitive and complex.

In most cases, the outcomes of our reviews show no evidence of deficiencies in how Victoria Police has conducted its investigation; however, that does not diminish the importance of our doing this work.

In cases where a deficiency is noted, the community can be confident that IBAC has made recommendations for redress or other action. Where no deficiency is noted, IBAC can play a vital role by giving feedback to Victoria Police on how to strengthen its processes to maintain integrity.

Investigations are often the public face of our oversight role. IBAC conducts investigations in response to complaints as well as conducting ‘own motion’ investigations. As this report shows, our investigations can involve considerable resources – one investigation alone involved the analysis of five and a half thousand documents. Where necessary, IBAC refers cases to independent, eminent former judges to ensure the utmost rigour and integrity. Such inquiries can extend for many months.

This report highlights some key achievements by IBAC in oversighting Victoria Police.